- Health

- Viruses, Infections & Disease

- Cancer

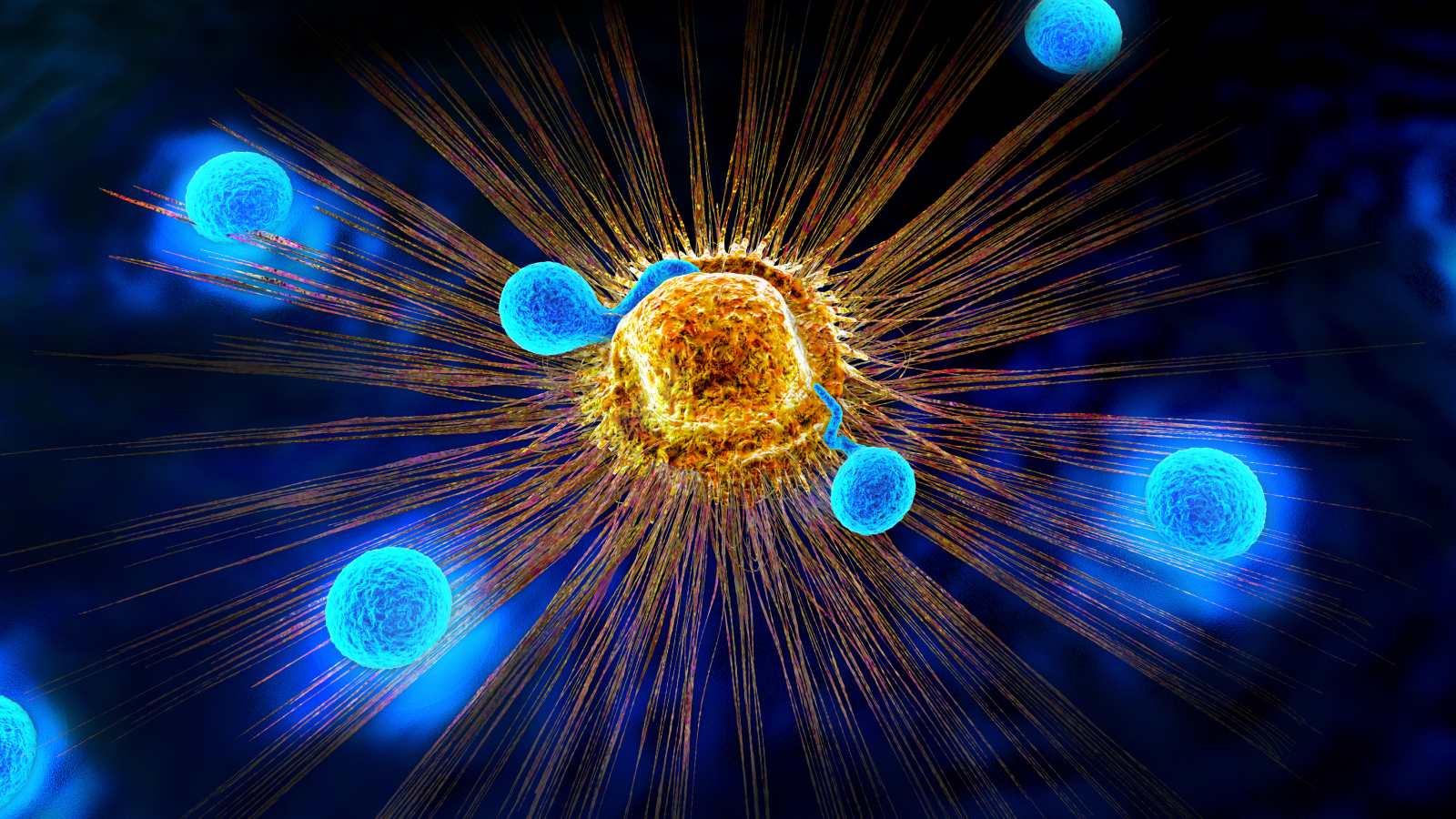

People with color blindness may be less able to spot an early sign of bladder cancer, making them likelier to be diagnosed later, a study suggests.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

People with color blindness and bladder cancer may face a poorer prognosis than those with bladder cancer and normal vision, a study has found.

(Image credit: lielos/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

People with color blindness and bladder cancer may face a poorer prognosis than those with bladder cancer and normal vision, a study has found.

(Image credit: lielos/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Could being colorblind make you less likely to survive bladder cancer? That's the surprising hypothesis that researchers have proposed based on a small study.

The research, published Jan. 15 in the journal Nature Health, examined data from 135 patients with both bladder cancer and color blindness, and compared those patients to 135 patients with only bladder cancer. The data were taken from TriNetX, an international registry of electronic health records of more than 275 million patients.

You may like-

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

-

These genes were thought to lead to blindness 100% of the time. They don't.

These genes were thought to lead to blindness 100% of the time. They don't.

-

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

The study authors suggested a plausible reason for this observed difference: Color blindness may make it more difficult to spot blood in your urine — an early sign of the cancer — thereby delaying diagnosis.

"Bladder cancer is a bad disease. If you delay your diagnosis, it will make a difference to your prognosis," Dr. Veeru Kasivisvanathan, a urological oncologist and surgeon at University College London who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

A possible link

Blood in urine is one of the most common early symptoms of bladder cancer, alongside frequent urination; pain or burning during urination; feeling as if you need to urinate even if your bladder isn't full; and urinating frequently during the night.

If anyone spots blood in their urine, they should see their doctor straight away, Kasivisvanathan said. But, as the study authors suggested, being unable to clearly distinguish red from yellow could make it very difficult to spot this early warning sign.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.Color blindness, also known as color vision deficiency, is a fairly common condition with one recent study reporting that about 1 in 40 people globally have some form of color vision deficiency. (Those figures are likely approximate, as screening for color vision deficiency is often not routine.) Color vision deficiency tends to be more common in males than in females, per the study.

The results of the new study should be taken with extreme caution, Kasivisvanathan and Shang-ming Zhou, a professor in e-health at the University of Plymouth who wasn't involved in the work, told Live Science. Indeed, the study authors also acknowledged that there are major limitations to their research.

For instance, because color blindness often goes undiagnosed, it's possible that some people with the condition were mistakenly added to the cohort without color blindness in the analysis, potentially muddying the results. The term "color blindness" also encompasses various conditions with different red-perception abilities. Protanopia (red-blindness) should theoretically carry a higher risk than deuteranopia (green-blindness) in this context, but the study cannot differentiate between these subtypes, said Zhou.

You may like-

These genes were thought to lead to blindness 100% of the time. They don't.

These genes were thought to lead to blindness 100% of the time. They don't.

-

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

-

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

In addition, the study was very small, which makes the results less dependable, and makes it difficult to screen for other factors that could explain the difference in prognosis. Lastly, from these data alone, it's not possible to prove that color blindness delayed the diagnosis of the disease; for now, that is just a hypothesis.

"The authors properly frame this as the hypothesis-generating work," Zhou said. "Current evidence is insufficient to recommend routine blood cancer screening in [patients with color vision deficiency], and the absolute risk increase remains unclear," he emphasized.

RELATED STORIES—Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

—'Disappearing' Y chromosome in aging men may worsen bladder cancer, mouse study shows

—Why is color blindness so much more common in men than in women?

In short, more research is needed to confirm that color blindness raises the risk of death from bladder cancer, and to evaluate how those patients might be better protected, if that's the case. Still, this is "the right type of [study] design for that type of question," Kasivisvanathan said, adding that while the research is not conclusive, it does open up interesting areas for investigation.

It could be that patients with known risk factors for bladder cancer — such as being a male over the age of 50, smoking, using blood thinners, or having a history of radiotherapy — might benefit from being warned about the potential risk of having undiagnosed color blindness on top of their other risk factors. And perhaps those with known color blindness and cancer risk factors could be encouraged to screen their urine in other ways, such as using test strips, Kasivisvanathan said.

This study also raises questions about other cancers that are associated with blood in bodily fluids in their early stages, such as oral cancers, Zhou added. But for now, more research is needed, all of the experts said.

DisclaimerThis article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Marianne GuenotLive Science Contributor

Marianne GuenotLive Science ContributorMarianne is a freelance science journalist specializing in health, space, and tech. She particularly likes writing about obesity, neurology, and infectious diseases, but also loves digging into the business of science and tech. Marianne was previously a news editor at The Lancet and Nature Medicine and the U.K. science reporter for Business Insider. Before becoming a writer, Marianne was a scientist studying how the body fights infections from malaria parasites and gut bacteria.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more These genes were thought to lead to blindness 100% of the time. They don't.

These genes were thought to lead to blindness 100% of the time. They don't.

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

A man's bladder looked like a Christmas tree

A man's bladder looked like a Christmas tree

'Chemo brain' may stem from damage to the brain's drainage system

Latest in Cancer

'Chemo brain' may stem from damage to the brain's drainage system

Latest in Cancer

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Science history: Female chemist initially barred from research helps develop drug for remarkable-but-short-lived recovery in children with leukemia — Dec. 6, 1954

Science history: Female chemist initially barred from research helps develop drug for remarkable-but-short-lived recovery in children with leukemia — Dec. 6, 1954

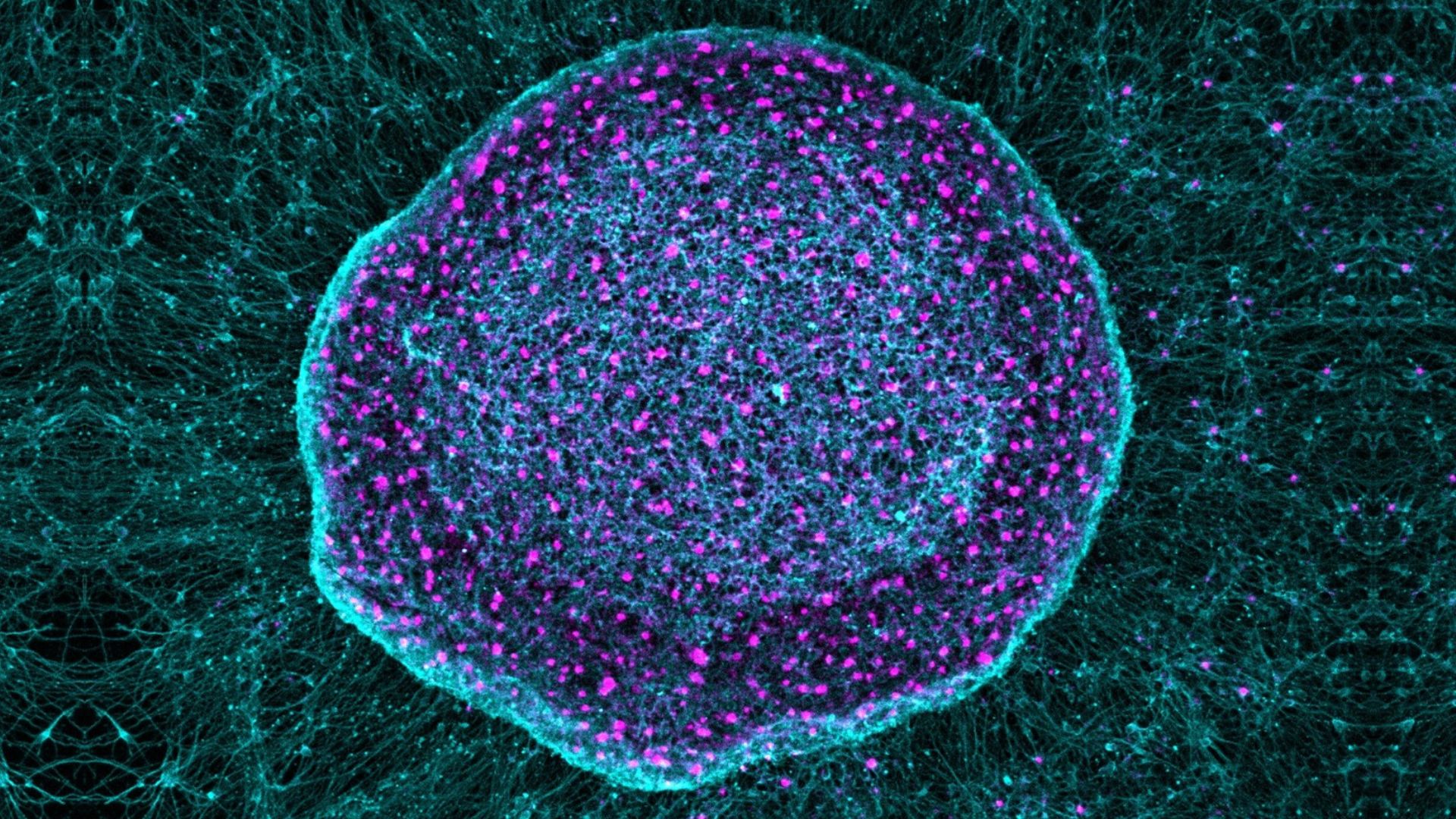

High-fiber diet may 'rejuvenate' immune cells that fight cancer, study finds

High-fiber diet may 'rejuvenate' immune cells that fight cancer, study finds

'Chemo brain' may stem from damage to the brain's drainage system

Latest in News

'Chemo brain' may stem from damage to the brain's drainage system

Latest in News

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

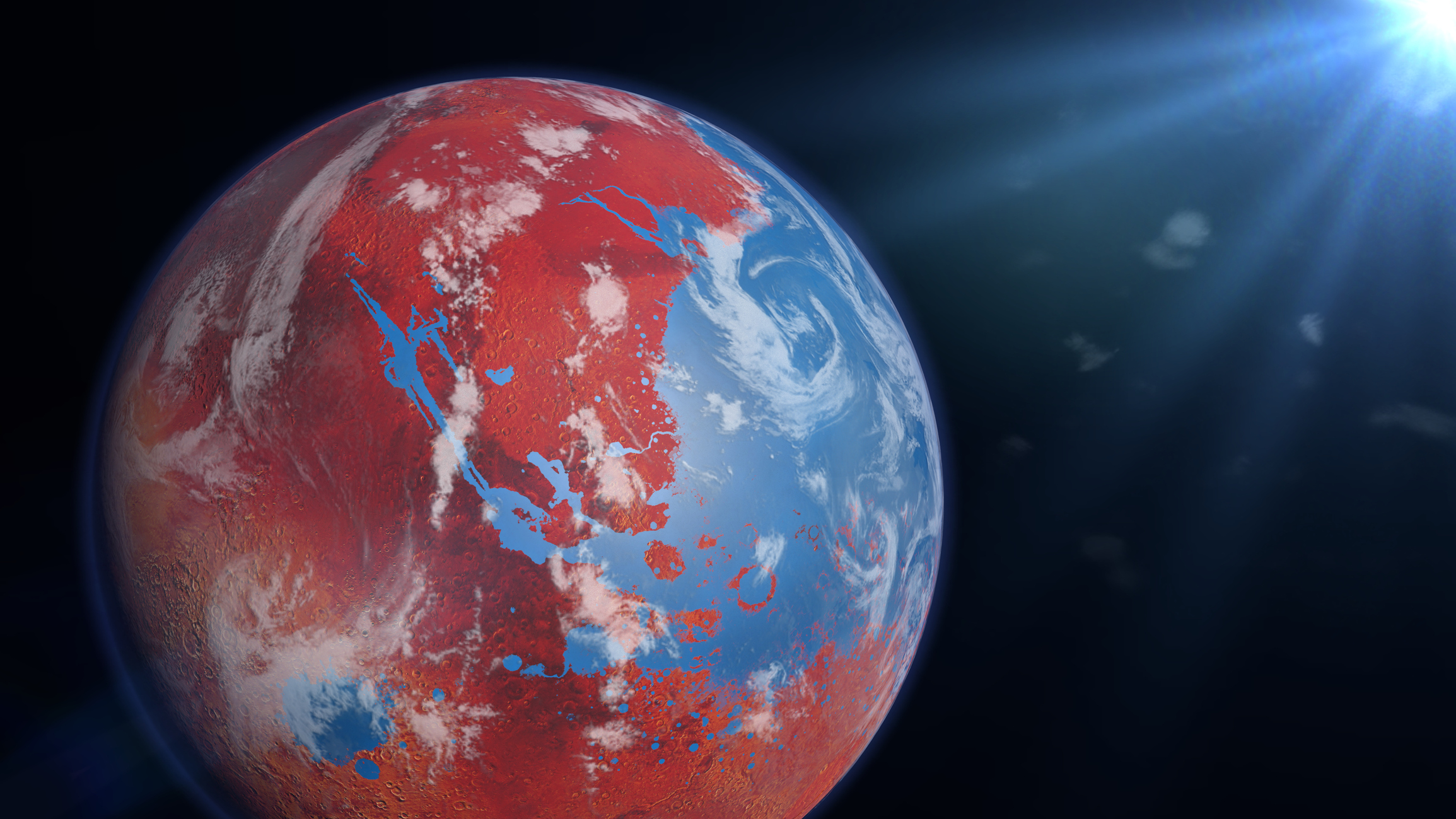

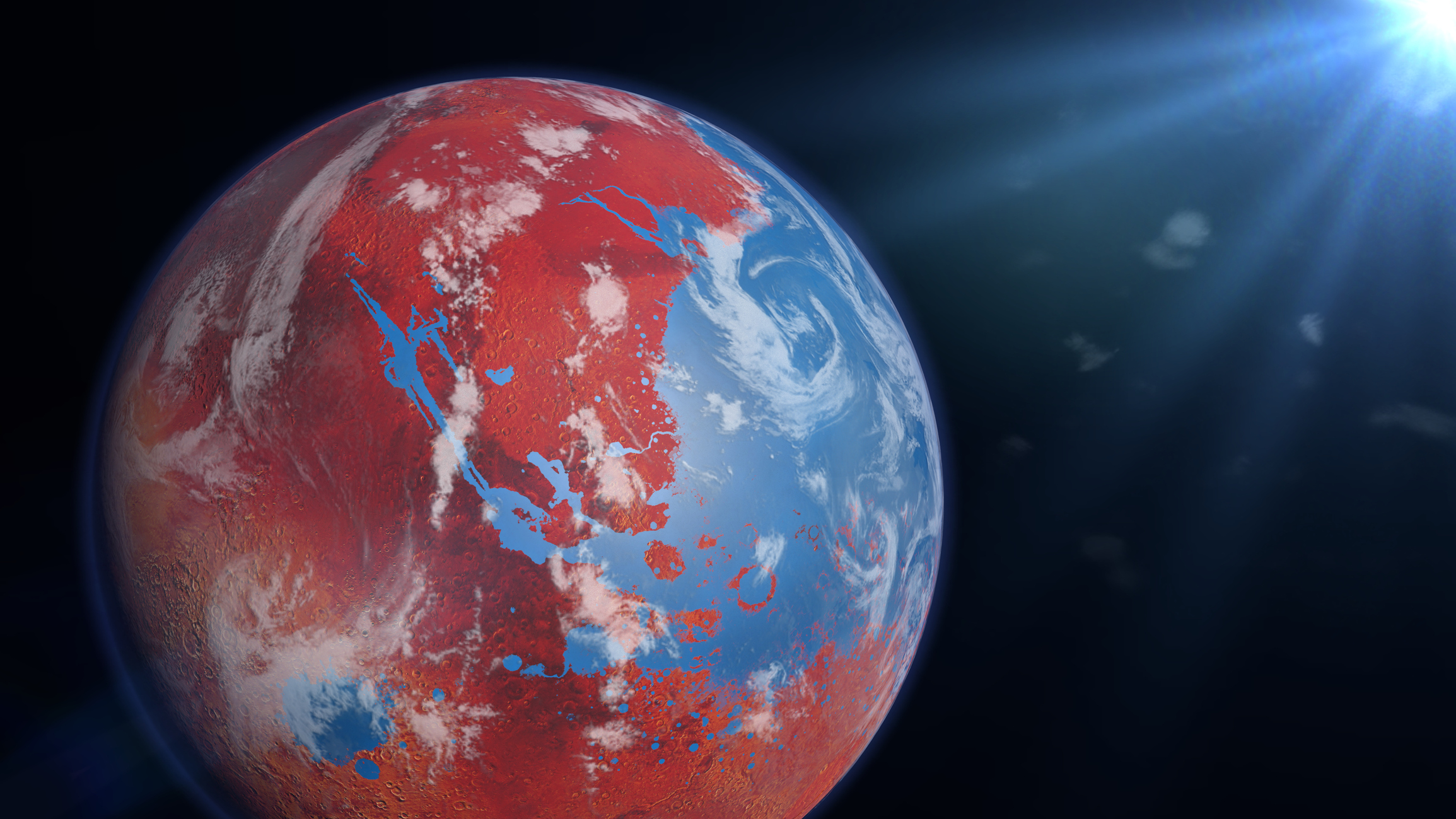

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

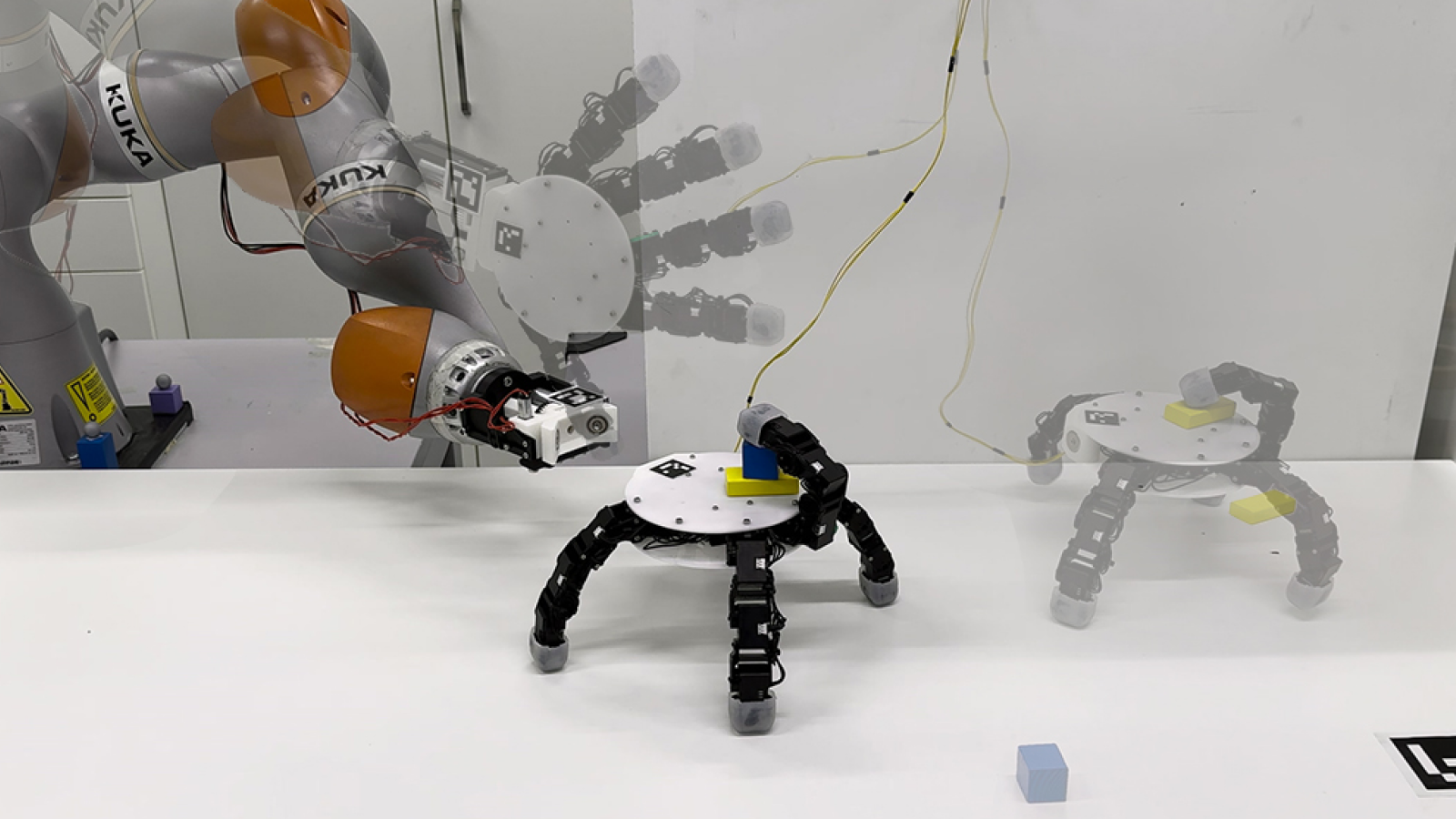

Creepy robotic hand detaches at the wrist before scurrying away to collect objects

Creepy robotic hand detaches at the wrist before scurrying away to collect objects

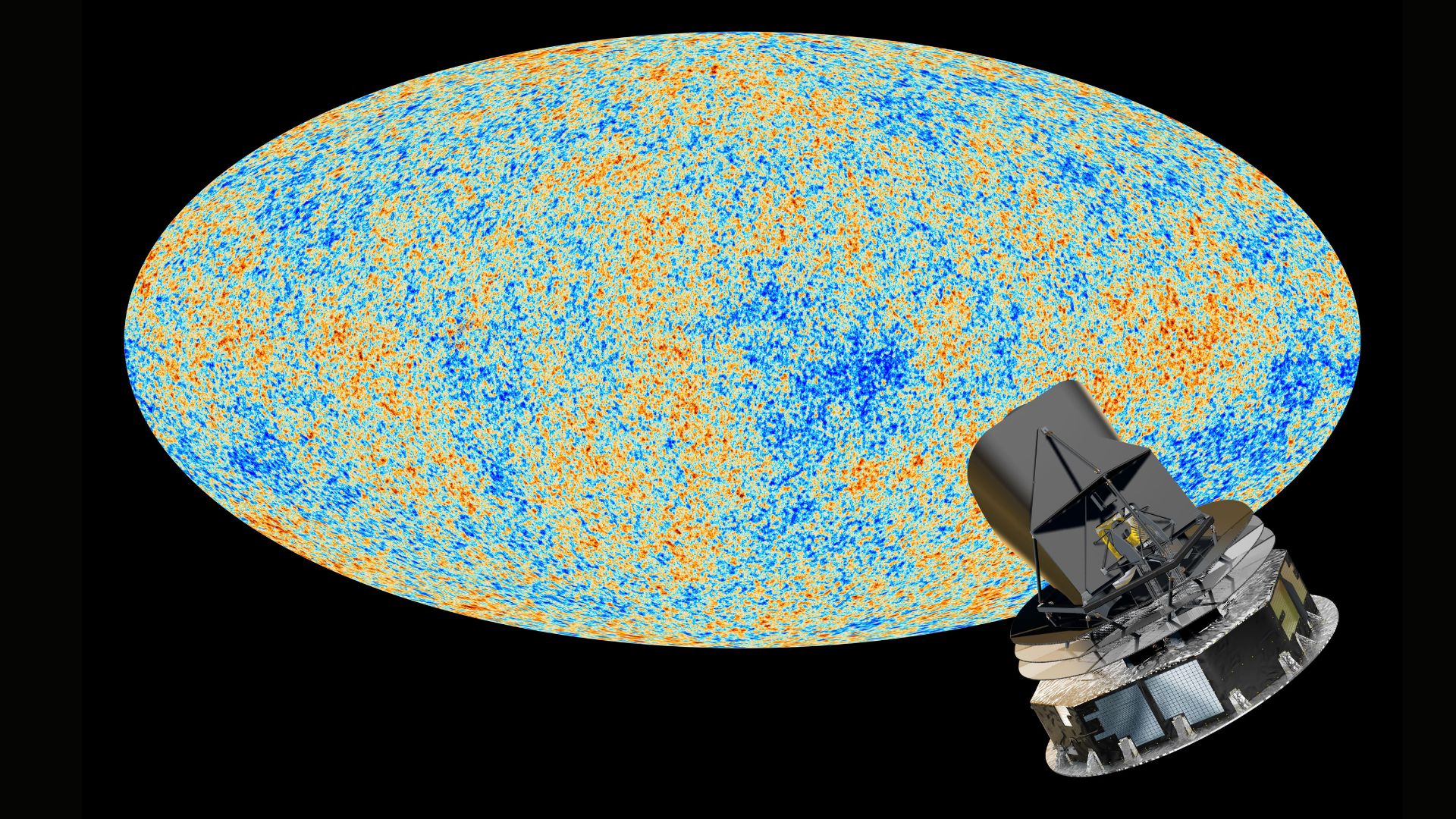

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

LATEST ARTICLES

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

LATEST ARTICLES 1An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

1An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint- 2'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

- 3Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

- 45,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

- 5Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works