- Health

A mouse study suggests estrogen may increase gut pain by activating specific cells, offering hints to why IBS is more common in women than in men.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

A new mouse study hints at one reason why women tend to be diagnosed with IBS more often than men.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

A new mouse study hints at one reason why women tend to be diagnosed with IBS more often than men.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Differences in how gut cells respond to hormones may help to explain why women experience more frequent and severe gut pain than men do, a study in mice suggests.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects roughly 10% to 15% of people worldwide, with women getting diagnosed with the condition up to twice as often as men do. Symptoms of IBS — which include pain, constipation, diarrhea, gas and bloating — can often flare up in response to triggers, like stress or certain foods. But the reasons behind the disparity between women's and men's IBS rates have remained elusive.

You may like-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

-

What causes the feeling of 'butterflies' in your stomach?

What causes the feeling of 'butterflies' in your stomach?

-

'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

"We've long suspected that female hormones play a role in gut pain, but the exact mechanism was unclear," senior study author David Julius, a neurophysiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, told Live Science. "Our findings show a clear pathway for how estrogen can amplify pain signals."

The study, published Dec. 18 in the journal Science, first compared gut pain responses in male and female mice by recording nerve activity in response to gut stimulation and observing their reactions to mild colon inflation. Both tests showed that female mice had more sensitive guts at baseline.

Removing the mice's ovaries to stop estrogen production reduced this sensitivity to male-like levels, however. And restoring estrogen to normal levels brought back the increased pain response seen in female mice.

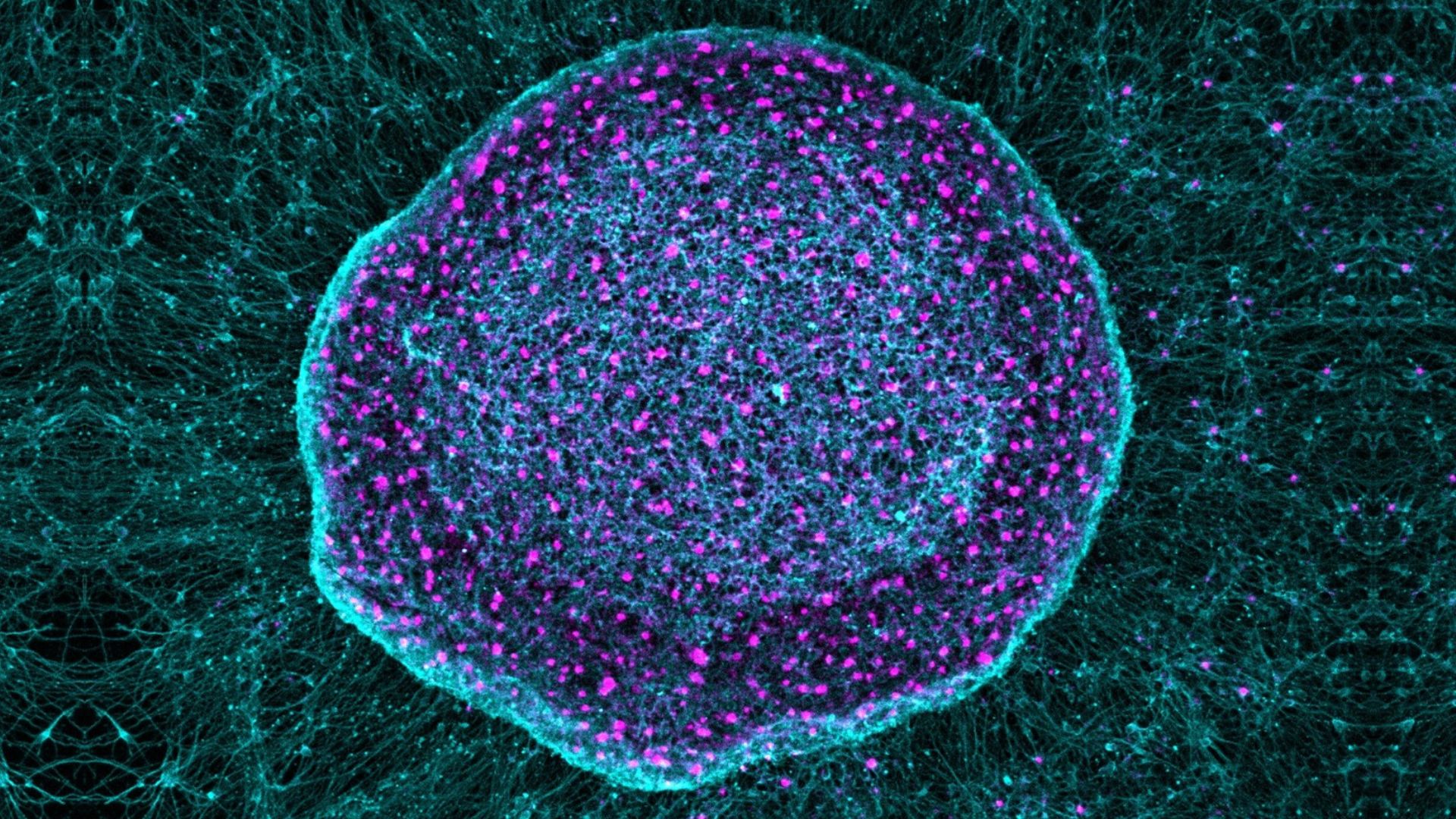

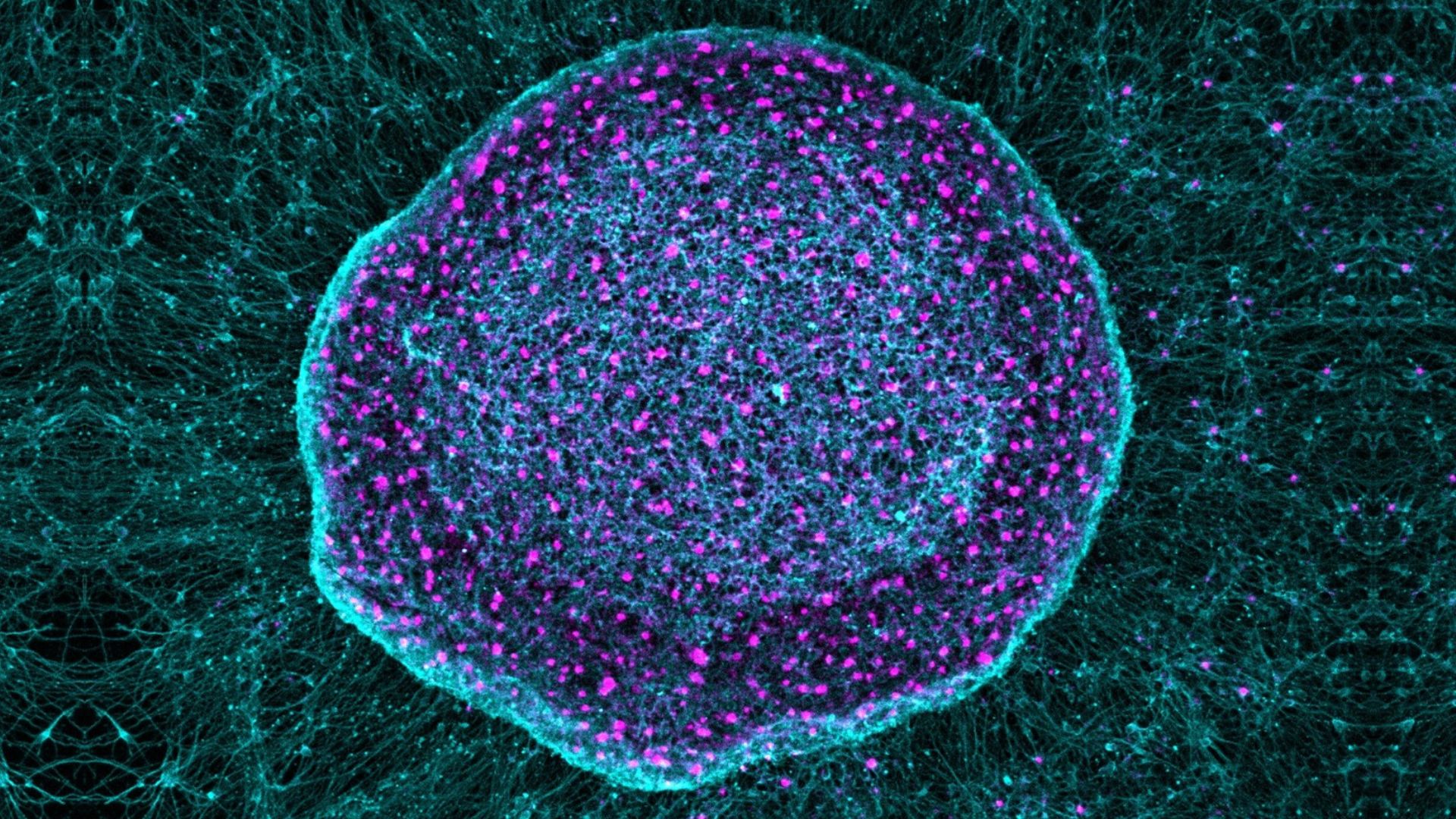

To find out where and how estrogen exerts its effects, the team examined different gut cells. Based on earlier work, they expected estrogen receptors to be on enterochromaffin cells, which produce about 90% of the body's serotonin, a chemical messenger involved in activating pain-sensing nerves that send signals to the brain. But surprisingly, the team found estrogen receptors not on enterochromaffin cells, but on specialized, rare cells in the lining of the gut.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.When these cells, known as L-cells, detect estrogen, they crank up their production of a receptor called OLFR78. This receptor senses short-chain fatty acids, which are byproducts made when gut bacteria digest food. The addition of extra receptors makes L-cells more sensitive to these byproducts, and in turn, they release more of a hormone that helps tell the brain that the stomach is full immediately after a person eats.

To better understand this chain reaction, the researchers grew miniature models of the gut in the lab. They found that the fullness hormone, called PYY, also signals nearby enterochromaffin cells that then release extra serotonin. That serotonin then activates pain-sensing nerves. This chain reaction set off by estrogen may potentially explain why women experience more severe gut pain than men do.

Experiments in genetically engineered mice that lacked estrogen receptors on L-cells confirmed the cells' role in gut sensitivity, as those mice showed weaker nerve responses and reduced serotonin release compared with mice with intact receptors.

You may like-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

-

What causes the feeling of 'butterflies' in your stomach?

What causes the feeling of 'butterflies' in your stomach?

-

'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

"Since estrogen levels fluctuate with the menstrual cycle, this mechanism provides insight into the changes in IBS severity seen in women," said Marissa Scavuzzo, an assistant professor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine who was not involved in the study.

"It also validates the experiences of higher-estrogen or menstruating patients," she said, "which is important because differences in pain sensation in women have historically been overlooked or dismissed."

The findings, though preliminary, may also inform future therapies for gut pain. "PYY and OLFR78 could be promising targets for treating IBS in women," Julius suggested. The work may also help to explain why "low-FODMAP" diets, which aim to reduce the intake of sugars that feed gut bacteria, can ease IBS symptoms in some patients, he added.

Scavuzzo agreed that the work might point to promising treatments. "By pinpointing PYY and L-cell signaling, this study identifies concrete molecular targets that could guide more precise therapies for IBS," she said.

related stories—Brain signals underlying chronic pain could be 'short-circuited,' study suggests

—Mindfulness meditation really does relieve pain, brain scans reveal

—Do women have a higher pain tolerance than men?

Additionally, the study "highlights the importance of considering how hormonal changes influence IBS symptoms, not only in menstruating women but also in post-menopausal patients and those receiving hormone therapy as part of gender-affirming care."

Translating these findings from mice to people will require caution. Human guts are more complex than those of mice, and factors such as lifestyle, genetics and gut-microbe diversity can influence individuals' hormone-gut interactions.

"Mouse models give us a starting point," Julius said, "but clinical studies are essential before we can make firm conclusions about human gut pain."

DisclaimerThis article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Isha IshtiaqLive Science Contributor

Isha IshtiaqLive Science ContributorIsha Ishtiaq is a freelance medical and health writer with a B.S. (Hons) in Biotechnology and an M.S. in Biological Sciences. She specializes in creating clear, trustworthy content that connects science with everyday life. She believes effective health communication builds trust, supports informed decisions, and respects the real people behind every question.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

What causes the feeling of 'butterflies' in your stomach?

What causes the feeling of 'butterflies' in your stomach?

'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Heart attacks are less harmful at night. And that might be key to treating them.

Latest in Health

Heart attacks are less harmful at night. And that might be key to treating them.

Latest in Health

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

Lab mice that 'touch grass' are less anxious — and that highlights a big problem in rodent research

Lab mice that 'touch grass' are less anxious — and that highlights a big problem in rodent research

Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests

Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Why is flu season so bad this year?

Latest in News

Why is flu season so bad this year?

Latest in News

Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

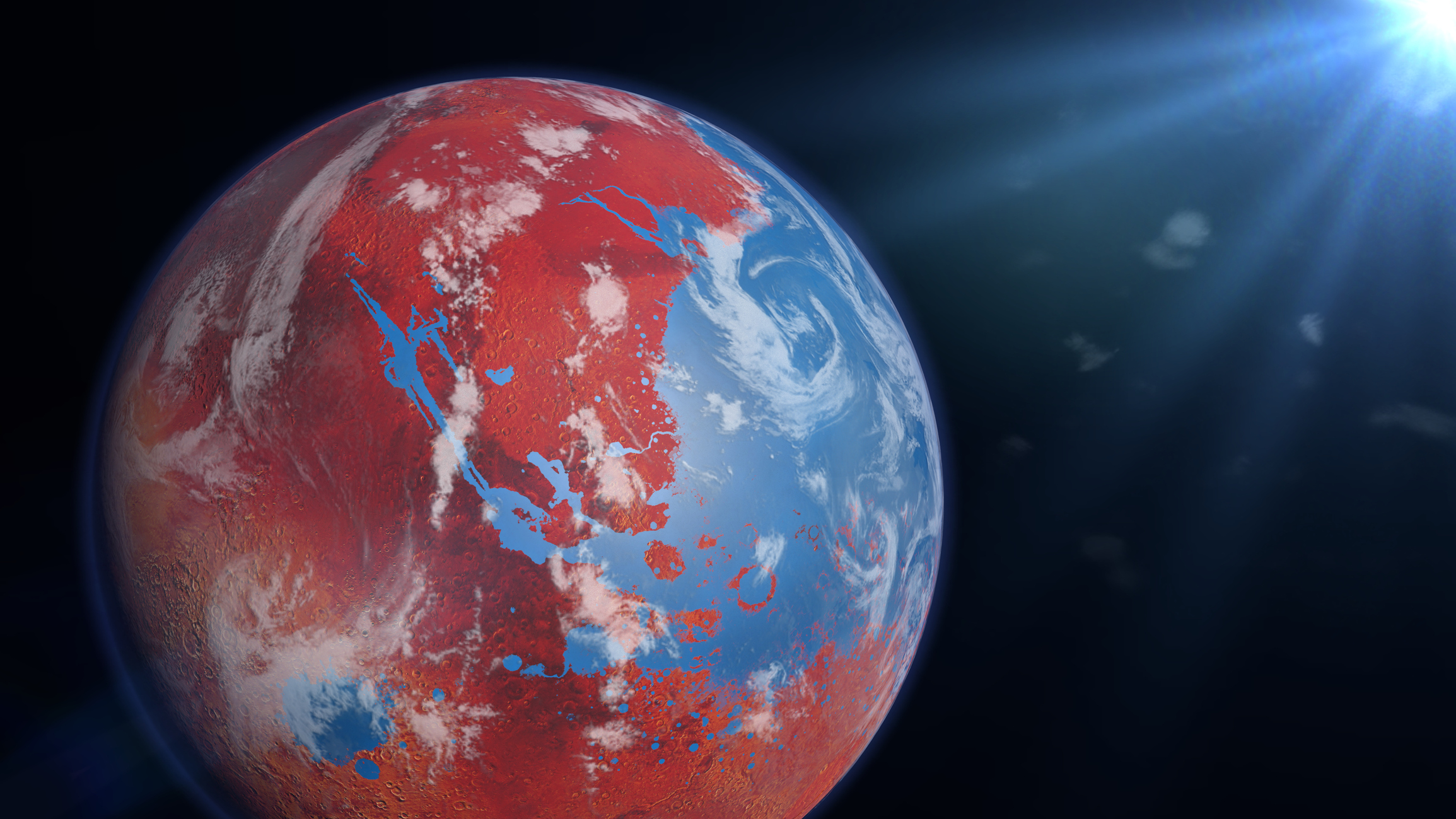

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

'Earthquake on a chip' uses 'phonon' lasers to make mobile devices more efficient

'Earthquake on a chip' uses 'phonon' lasers to make mobile devices more efficient

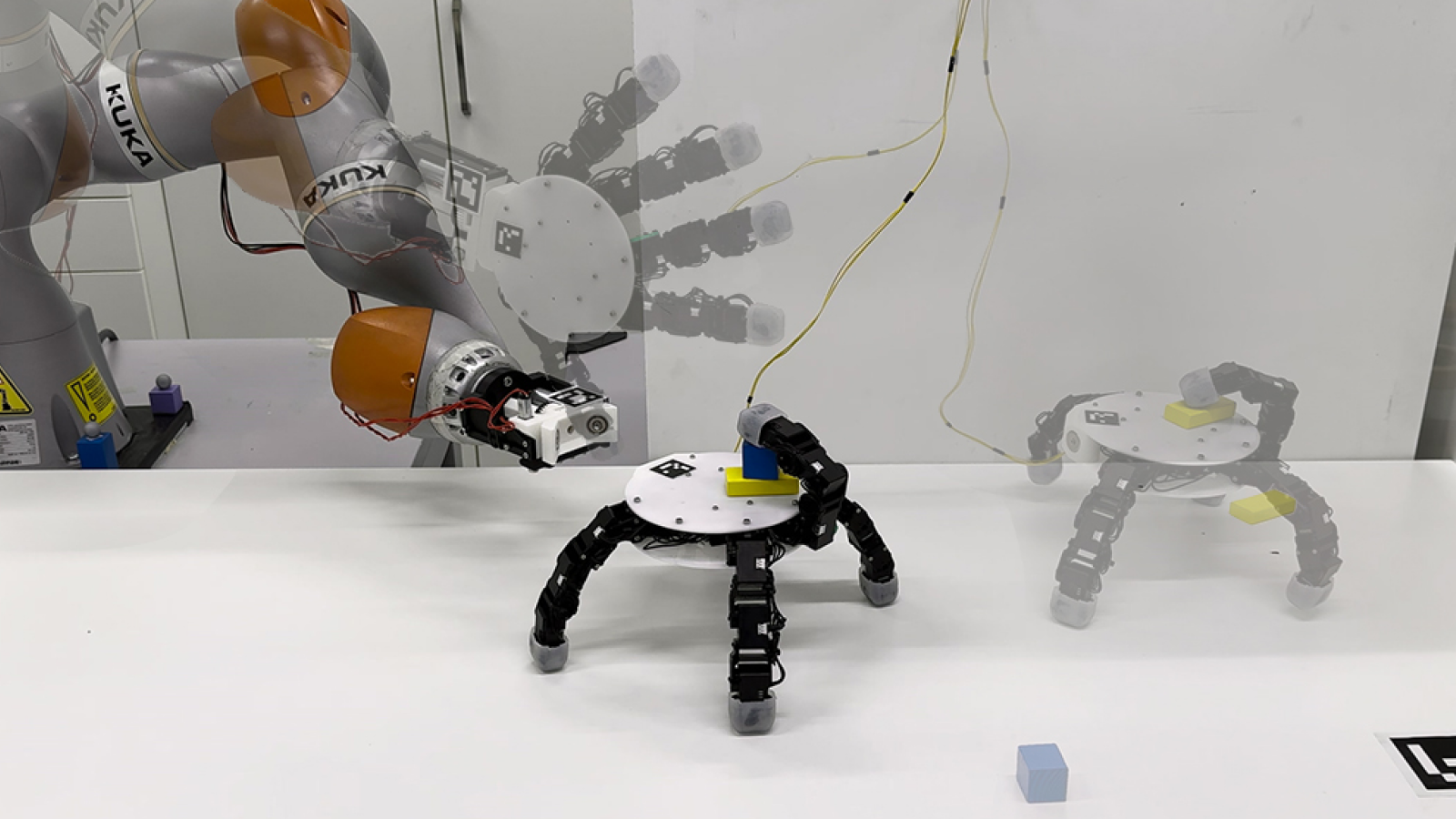

Creepy robotic hand detaches at the wrist before scurrying away to collect objects

Creepy robotic hand detaches at the wrist before scurrying away to collect objects

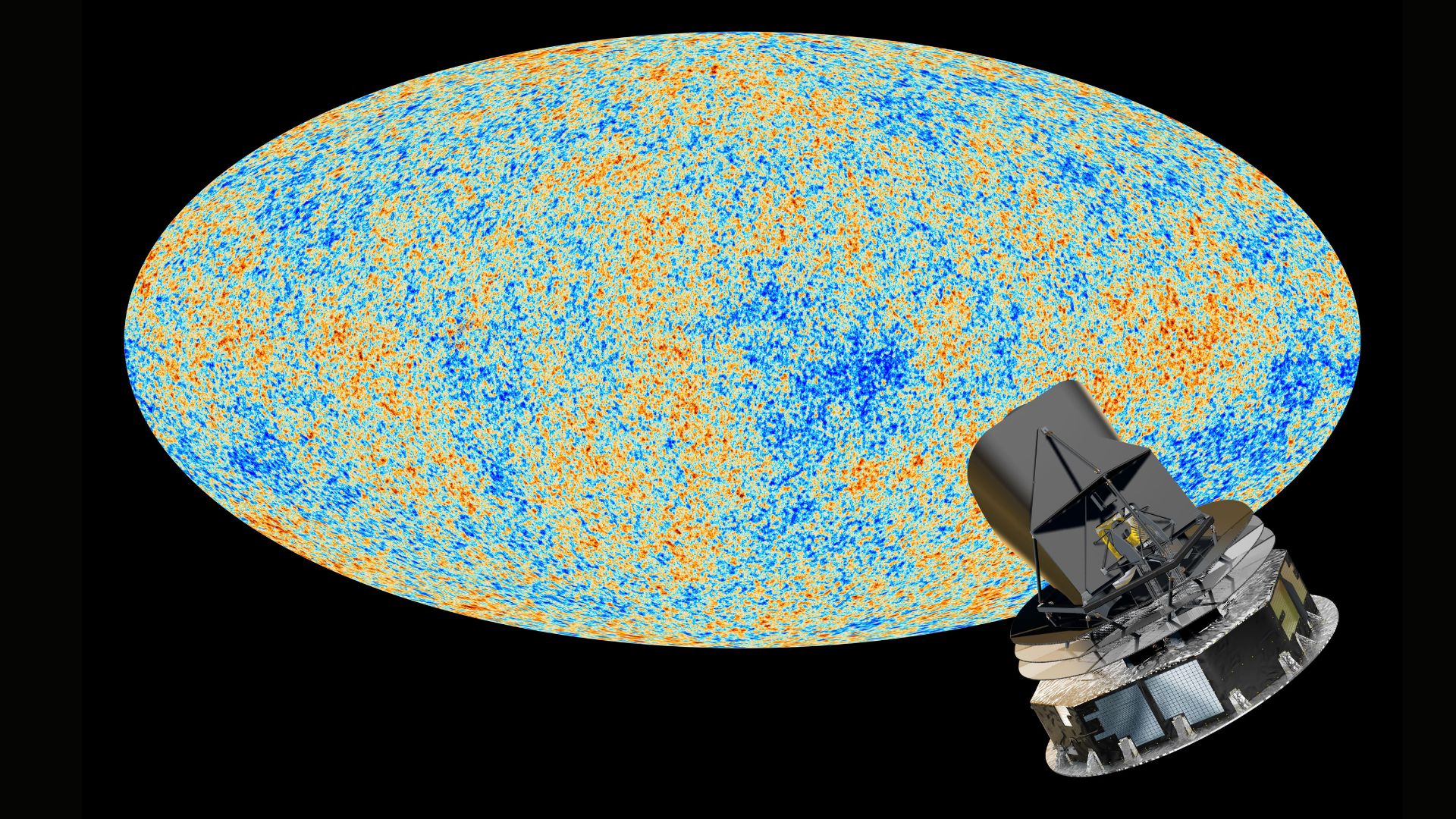

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

LATEST ARTICLES

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

LATEST ARTICLES 1Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

1Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago- 2'A real revolution': The James Webb telescope is upending our understanding of the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe

- 3'Earthquake on a chip' uses 'phonon' lasers to make mobile devices more efficient

- 4Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants

- 5How to choose the best dehumidifier for your home this season